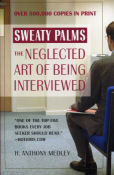

| What REALLY goes on in a job interview? Find out in the new revision of "Sweaty Palms: The Neglected Art of Being Interviewed" (Warner Books) by Tony Medley, updated for the world of the Internet . Over 500,000 copies in print and the only book on the job interview written by an experienced interviewer, one who has conducted thousands of interviews. This is the truth, not the ivory tower speculations of those who write but have no actual experience. "One of the top five books every job seeker should read," says Hotjobs.com. | |

| Fateless (8/10) by Tony Medley “Fateless” is exceptional. For anyone who wants to know what living through the Holocaust was like, this is the movie. In 1997, a particularly irritating film, “Life is Beautiful,” made the rounds and it was lionized. I thought it deplorable. It demeaned the Holocaust by showing life in extermination camps as relatively benign, sort of like “Hogan’s Heroes” demeaned the suffering endured by those in Nazi POW camps. Sure, “Life” was a heartwarming story of a father’s love and sacrifice for his son. But it could have done so and shown a much more accurate presentation of what life was really like in the camps and for the victims. That’s what “Fateless” does. Based on screenwriter Imre Kertész’s autobiographical novel, it is a brutal, no-holds-barred, telling of what life was like through the eyes of a 14-year-old Jewish boy, Gyuri Koves (Marcell Nagy), who is swept off the streets of Budapest in 1944 and condemned to life in the concentration camps. One of the many things that sets this apart from other Holocaust films is the cinematography of Lajos Koltai, who makes his directorial debut. The film is shot in color, but it emphasizes the bleakness of Gyuri’s’ life by showing much of the film in color that is so muted it might as well be in black and white. While, due to his youth, Gyuri is relatively dispassionate throughout the film, we see him slowly descend into a dehumanized being, living day to day, not even trying very hard to survive, just going with the flow. The way Gyuri is picked up to be delivered to the camp is horrifying in its seeming innocuity, another stark example of the banality of evil. There is no brutal roundup, but it happens with slow suddenness. Although done without urgency, the viewer knows that Gyuri is headed for oblivion, swept from his mother and stepmother without notice. This is a long movie, 140 minutes. While I don’t think any movie has any business exceeding 90 minutes, the length of this film has a purpose. It allows the audience to participate in the increasing agony and forlorn nature of life in a concentration camp. There were some surprising occurrences in this movie that opened my eyes. Gyuri kept being moved from camp to camp. I had thought camps like Auschwitz and Buchenwald were extermination camps, so I don’t understand why Gyuri is moved from one to another. Late in the movie he is taken to what looks like a camp hospital for treatment. In addition to treatment, he is allowed to be cleaned, to sleep alone in a bed and be cared for. Why would an extermination camp have a camp hospital? Wouldn’t they work them to the point of starvation and exhaustion and then gas them? At various points in the film Gyuri and his companions hang out together. Was security so lax in the camps that this was possible? These things bothered me enough to ask Mark Urman, Head of U.S. Theatrical for THINKFilm, the U. S. distributor if they were literary license. He responded acerbically, “This is all accurate and based on actual experience, and corroborated by other similar accounts, memoirs, and historical research,” adding, “Imre Kertész IS NOT James Frey.” I guess, in addition to losing Oprah, poor James can’t count on THINKFilm to distribute any film version of his now thoroughly discredited bestseller. Since these scenes are apparently based on fact, I guess we have to accept them, but they still seem inconsistent with the Final Solution. Frankly, I remain dubious. Although this is an outstanding film, and one I heartily recommend, the size of the audience indicates that I am not the only one who has had a surfeit of Holocaust films. I saw it on opening night, a Friday showing at 8:00 p.m. There couldn’t have been many more than 25 people in the theater. Contrasted with the abundant Holocaust films, how many films have there been about the Japanese bestiality to the people they conquered in World War II? I can think of two, “The Bridge on the River Kwai” (1957) and “King Rat” (1965). Neither showed the unspeakable brutality of the Japanese, personified by the Rape of Nanking, the Bataan Death March, and their subjugating hundreds of thousands of women into forced prostitution, calling them, “comfort women.” Two movies, neither of which are particularly damning, vs. hundreds of Holocaust movies. If they haven’t yet learned it from the marketplace, it’s time filmmakers declared a moratorium on Holocaust films. January 29, 2006 |

|

|

|

|