|

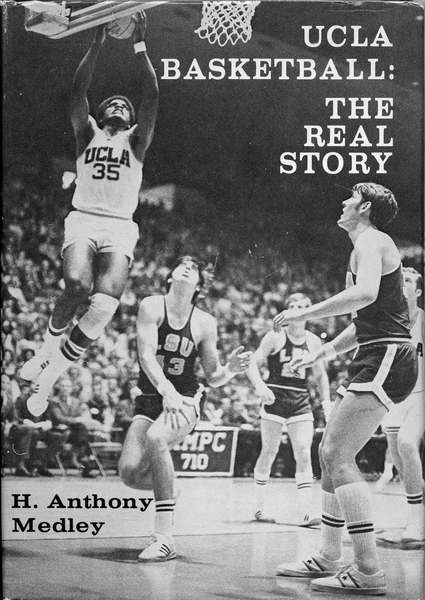

Out of print for more than 30 years, now available for the first time as an eBook, this is the controversial story of John Wooden's first 25 years and first 8 NCAA Championships as UCLA Head Basketball Coach. This is the only book that gives a true picture of the character of John Wooden and the influence of his assistant, Jerry Norman, whose contributions Wooden ignored and tried to bury. Compiled with more than 40 hours of interviews with Coach Wooden, learn about the man behind the coach. The players tell their stories in their own words. Click the book to read the first chapter and for ordering information. Also available on Kindle. |

|

Bridge of Spies (4/10) by Tony Medley Runtime 140 minutes. OK for children. Director Stephen Spielberg casts a sympathetic eye on a KGB soviet spy (which he had been since 1927), Rudolph Abel (Mark Rylance, who gives a bravura performance, the main reason for seeing this movie, equaling his work as Thomas Cromwell in the TV miniseries Wolf Hall), who was working to transmit U.S. military secrets to the most ruthless regime the world has ever seen, Soviet Russia. But according to Spielberg (and writers Mark Charman and Ethan & Joel Coen), he was a soft-spoken, mild-mannered guy more interested in painting than spying, just a guy working for his country. Well, Hitler and Dr. Mengele were also just guys working for their country. But Spielberg goes even further. He paints his hero, Jim Donovan (Tom Hanks), as an “insurance lawyer” who is appointed to defend Abel after Abel is arrested and put on trial for espionage. Spielberg presents Donovan as a guy who doesn’t know anything about spy trials. What Spielberg doesn’t tell you is that Donovan was a lot more than an “insurance lawyer.” From 1943 to 1945 he was General Counsel at the Office of Strategic Services. In 1945 he became assistant to Justice Robert H. Jackson at the Nurenberg trials in Germany. Donovan was the presenter of visual evidence at the trial. He was also an advisor for the documentary feature The Nazi Plan. So he was hardly the novice Spielberg and Hanks paint him to be. Spielberg is so at pains to draw a moral equivalence between spies of our enemies and our spies that he goes overboard to paint Abel sympathetically. Spielberg doesn’t let on that Abel arrived in the U. S. in 1948 and returned to the Soviet Union in 1955 for “rest and recreation,” and that upon his return to America he complained bitterly to the KGB that his assistant, Reino Häyhänen (not shown in the movie or even mentioned), be recalled to Moscow (for probable execution) because he wasn’t an effective spy. It was when Häyhänen discovered that the KGB was going to recall him, and probably execute him, that Häyhänen asked for asylum at the U.S. embassy in Paris and eventually turned Abel in to U.S. authorities. One of the more disconcerting parts of this film is that it not so subtly stands as a metaphor attacking U.S. actions in the Iraq wars, showing, for instance, captured U2 pilot Francis Gary Powers (Austin Stowell) being tortured by water. It seems to be Spielberg’s point of view that even though one is an enemy and working for the destruction of our way of life, he’s just another guy working for the good of his country and its way of life, so who are we to condemn, even though that way of life is a brutal dictatorship? Equally disturbing is its depiction of Rudolph’s trial as equivalent to Soviet show trials by representing Judge Mortimer Byers (Dakin Matthews) as thoroughly corrupt in that he is shown to have made up his mind before the trial starts, going so far as to instruct Donovan in a pre-trial meeting in Chambers not to make a big deal out of his defense. So Spielberg makes it clear that going through with the trial in his film was little more than a charade, and that there’s little difference between justice in U.S. courts than in a Nazi court or a Soviet court. The pace of the first hour is so slow it fits in with Spielberg’s work over the past several decades during which he has completely lost touch with pace and a realistic time to tell a story. It picks up a little when Donovan goes to East Germany to negotiate for the release of Powers, but it still drags on interminably, burdened by the insertion of a contrived device of Donovan suffering from a cold the entire time he was in Germany. This would be a good tale if Spielberg had just told the story straight up in 90 minutes without trying to influence the audience to his point of view. All in all, this is a film of which the Hollywood Ten would be proud. But even they would need some NoDoz. |

|

|