|

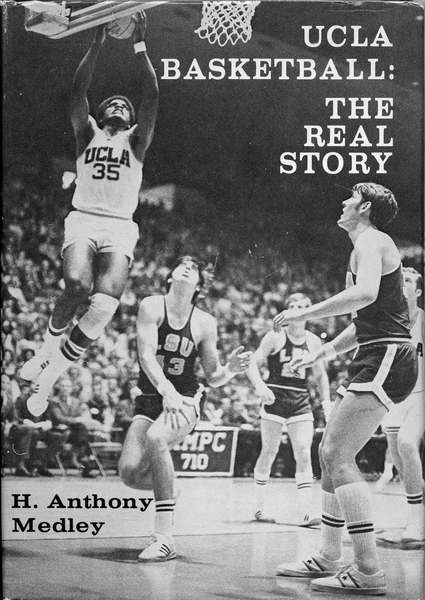

Out of print for more than 30 years, now available for the first time as an eBook, this is the controversial story of John Wooden's first 25 years and first 8 NCAA Championships as UCLA Head Basketball Coach. This is the only book that gives a true picture of the character of John Wooden and the influence of his assistant, Jerry Norman, whose contributions Wooden ignored and tried to bury. Compiled with more than 40 hours of interviews with Coach Wooden, learn about the man behind the coach. The players tell their their stories in their own words. This is the book that UCLA Athletic Director J.D. Morgan tried to ban. Click the book to read the first chapter and for ordering information. Also available on Kindle. |

|

City of Life and Death (8/10) by Tony Medley Run time 133 minutes Not for children. I’ve written about the Japanese bestiality before and during World War II, so was heartened to see that someone was finally making a movie about the Rape of Nanjing. This is a well-made, terrific exercise in telling a story of horror that I highly recommend, with qualifications. That said, one must be steeled for it because what happened in Nanjing is truly horrible. I’ve seen photographs of a woman being tortured in a public square in Nanjing during the assault. They were so horrible I won’t reveal what they did to her, but it’s seared in my memory. I have no way of knowing how accurate this telling is, but some of it is even worse than I had imagined. Unfortunately, writer-director Lu Chuan minimizes the agony of comfort women. One scene infuriated me. One of the Japanese soldiers visits a comfort woman (for your information, a “comfort woman” was a palatable word the Japanese substituted for what they really were, sex slaves). She’s a gorgeous Asian living in what looks like a comfortable bedroom. She’s gentle and tender and when she finds he’s a virgin, she gently and lovingly initiates him. This is pure hogwash. “Comfort women” were never Japanese. They were from conquered peoples, mostly Chinese and Korean. And they lived a life of hell, providing forced sex day after day after day with no respite. Check out my articles Japanese and the Comfort Women, http://www.tonymedley.com/Articles/Japanese_and_the_Comfort_Women.htm and Rape and Japanese Hypocrisy, http://www.tonymedley.com/Articles/Rape_and_Japanese_Hypocrisy.htm; to see what their lives were really like. As I said in these articles, just think how horrible it would be to be captured by a conquering Japanese army and sentenced to continuous sexual slavery, forced to perform sex acts on and with men, many of whom were full of venereal disease, 12-18 hours a day, maybe several an hour, seven days a week...by the de facto government, with no end in sight! It’s reported that in one comfort station in Burma comfort women were forced to have intercourse with sixty men in a single day. It apparently was not unusual in comfort stations for enlisted men for women to have to have intercourse twenty to thirty times a day. And this was the fate of hundreds of thousands of innocent women, many of whom were virginal teenagers when captured and enslaved. This whitewash of one of the Japanese most brutal policies is a major weakness of the film and it’s puzzling that a Chinese director would take this revisionist point of view. Worse, he shows a scene where women are asked to “volunteer” to become comfort women to save others. While I don’t know what actually happened, and while this could be true, I doubt the veracity of this scene because the Japanese were total conquerors and didn’t need to have women “volunteer” to be comfort women. The Japanese were as unsympathetic to the people they conquered as Genghis Khan’s Mongols. They considered conquered peoples already dead and treated them that way. This film is like looking at a black and white documentary, even though it isn’t (it is black and white, although on wide screen; it’s not a documentary). The battle scenes, brilliantly filmed by director of photography Cao Yu, make you feel like you are in the middle of them. The Japanese cruelty is grim and severe. There are no velvet gloves used here for the way they treated their conquered peoples, except for the way the film deals with comfort women. The first hour is told, sort of, through the eyes of a Chinese soldier and a child soldier he has befriended. The rest of the film is about the people in a refugee camp and how they were treated by the Japanese. While this is a first class film that tells a story that has begged to be told for ¾ of a century, I can’t really encourage people to go and see it without the caveat that it is harsh and depressing. As indicated above, however, it is not totally anti-Japanese. While it shows their breathtaking brutality, it takes a nuanced view that the genocide was a dehumanizing experience that negatively affected everyone, Chinese victims and Japanese oppressors alike. Lu Chuan said he changed his mind after interviewing some of the Japanese soldiers who took part in the Rape of Nanking. These monsters apparently convinced him that they were victims of their own inhuman brutality, too, so he made his film in a way that minimizes the blame a viewer casts on the Japanese. That’s pretty controversial for anyone who knows how the Japanese treated the people they conquered and captured everywhere, not just in Nanjing. Along those lines, it is slightly reminiscent of Clint Eastwood’s deplorable Letters from Iwo Jima (2006) that showed the rabid, ruthless Japanese of Iwo Jima as just regular guys, morally equivalent to the American Marines and GIs who were fighting to liberate the Pacific. Painting the cruel, heartless Japanese who murdered 300,000 innocents in Nanjing with any kind of even-handed sympathy is something I buy even less than I bought Eastwood’s revisionist view of the men who fought on Iwo Jima. Even so, with my proviso, this is a movie that should not be missed. People should not forget what happened in Nanjing, and the vast majority probably aren’t even aware of it, apart from the term “The Rape of Nanking.” This film turns the phrase into stark reality. In Mandarin, Japanese, English, and Shanghainese. June 6, 2011 |

|

|